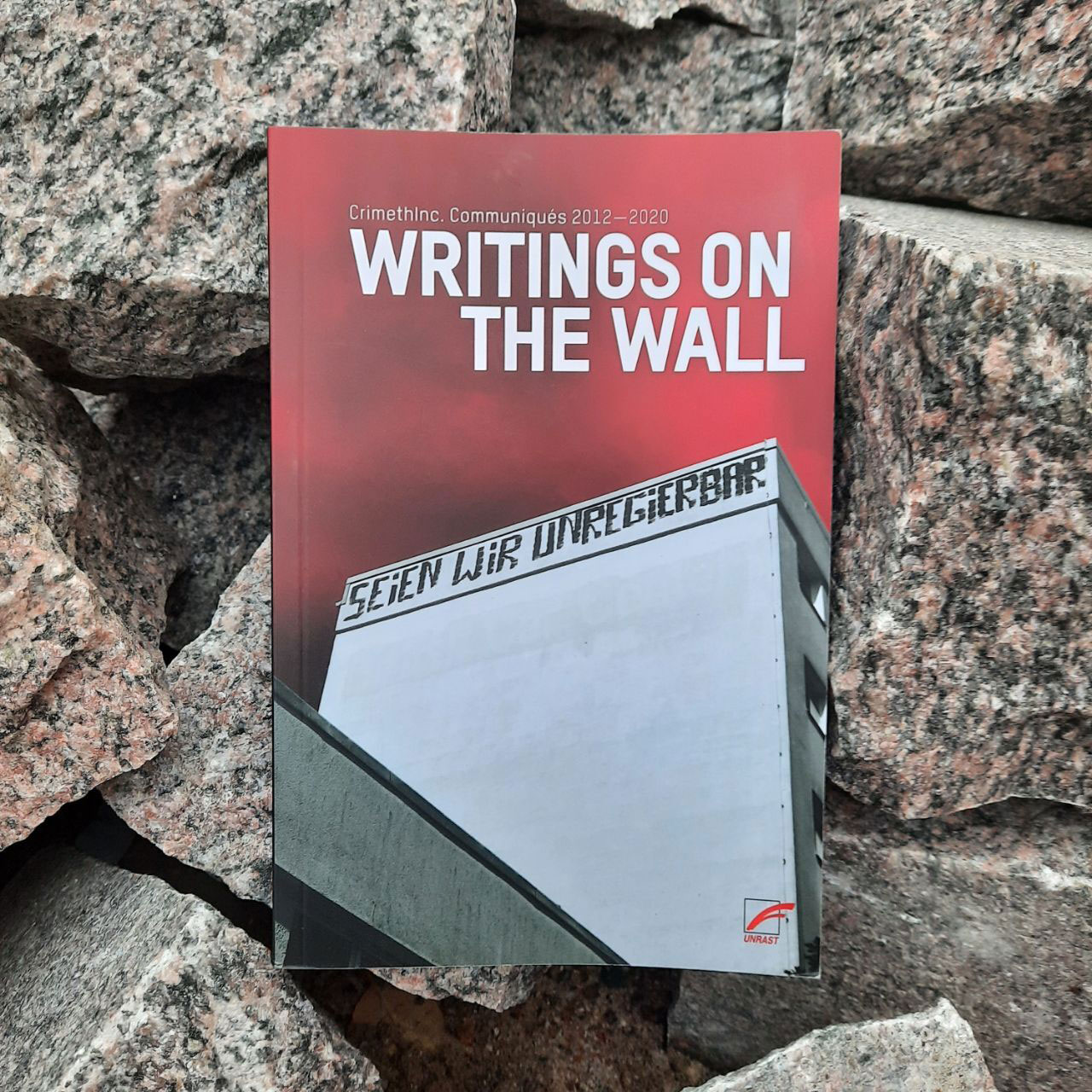

Working with the German publisher Unrast, our friends from Black Mosquito have published a collection of our writing from 2012-2020 in German, entitled Writings on the Wall. Together, these texts offer a view from the front lines of struggles from Minneapolis to Kurdistan, exploring some of the most urgent subjects of debate in contemporary social movements—violence, vengeance, consent and consensus, how to persevere in the face of seemingly impossible odds, what revolution could mean in the 21st century. In the introduction, presented below in English, we describe the times and conditions we were writing in and what our experiences might offer the struggles of the future.

The German version of this page will be updated on an ongoing basis with information about presentations, reviews, and readings of the book. The contents of the book are listed after the introduction.

First Principles

No government possesses inherent authority. No contract, procedure, or tradition has any legitimate claim on us beyond what we agree to voluntarily. No law should override our consciences. Rather than offering some version of the Nuremberg defense to excuse our decisions—be it religious, political, economic, or legal—we must take personal responsibility for the impact that our actions have on the world.

History is not an inexorable process that plays out according to iron laws. It is the chaotic conjuncture of innumerable forces including our own agency. “Theory” has no value except as a set of hypotheses we continuously test and refine in the course of our efforts to intercede in events. Revolutionary analysis must not be not the domain of a priest class that cites Marx the way earlier ideologues cited the Bible. It can only belong to those who learn about the world in the process of attempting to change it.

When we act, we act without guarantees. We cannot be certain of the result in advance; the end of this story has yet to be written. We risk everything because we know that death is inescapable, but to live—to achieve the full unfolding of our collective potential in spite of a social order that isolates and stunts us—to live is the rarest thing of all.

This is what we mean when we say that we are anarchists.

We believe that it is most ennobling to engage with other people as equals rather than as authorities to obey or subjects to rule. Let there be no one above us—and no one below. We believe that everyone stands to gain from the abolition of hierarchies, even those who ostensibly benefit from them, for in alienating us from each other and from what is most beautiful in ourselves, they drain our lives of meaning. For us, anarchism is not the blueprint of a possible future world, but the necessity of immediately taking sides in the conflicts that are taking place today—with the aim of disabling the mechanisms that impose disparities and seeking to foster self-determination and solidarity wherever they can take root.

In our experience, ungovernable grassroots movements that rely on direct action are far more efficient and effective than legalistic top-down campaigns that set out to win reforms. If we limit ourselves to petitioning our rulers for change, there will always be rival petitioners who can bribe them more effectively than we can. It is only when we show that we are capable of bringing about the changes we want directly that politicians come running after us offering to grant the concessions they fear we will take by force. Of course, if we can make the changes we wish to see ourselves, we don’t need rulers in the first place.

We saw this confirmed yet again shortly before this book went to press when rebels burned down the Third Precinct of the Minneapolis police in response to the murder of George Floyd. Until people saw rioters defeat the police by main force, it was unthinkable that mainstream political discourse in the United States could ever entertain the proposal to abolish police. Afterwards, police abolition became a widespread discussion topic, forcing liberals to try to undermine the movement against police by watering it down from within.

Our greatest obstacle is that we don’t know our own strength.

The Times We Wrote in, the Times to Come

This book brings together a selection of our work from 2012 to 2020.

Our collective has been publishing since the early 1990s. A quarter of a century ago, when we embarked on this project, anarchism manifested itself chiefly as a refusal of paradise. Neoliberal capitalism and state democracy appeared to have triumphed in what Francis Fukuyama called “the end of history,” but we—willfully damned souls—rejected the utopia they offered us as a mirage. “Better self-determination in hell than service in heaven,” we declared, like Milton’s Satan, refusing to sell ourselves on the market and eking out a precarious existence in the margins.

Fukuyama and his cronies thought they were finished with history, but history was not finished with them. As we warned, a global system driven by the imperative to turn a profit can only progressively impoverish the vast majority of humanity while concentrating power in the hands of the most rapacious. Today, the disastrous effects of neoliberal capitalism are plain for all to see, and more and more people are taking up the tactics we spent decades refining.

In the interceding years, we have developed networks spanning five continents and dozens of languages. Together, we try to think through the strategic questions confronting us, comparing our experiences in different struggles and contexts in order to formulate new proposals to employ in social movements. Like the global anarchist movement as a whole, we have no party line, only the intellectual biodiversity of debate and the shared determination to create a world in which no human being may rule another.

The last global wave of revolt arrived hot on the heels of the last recession. It opened with the Greek insurrection of December 2008, a precursor of the so-called “Arab Spring” and the various Occupy movements. Arguably, it concluded in 2014 with nationalists hijacking the uprisings in Brazil and Ukraine and with the militarization and ultimate defeat of the revolutionary movement in western Syria. In our book From Democracy to Freedom, we explored some of the limits that these movements reached as a result of focusing on trying to legitimize new institutions of governance rather than seeing the revolt through to its logical conclusion.

For six years, we have reaped the bitter harvest of this defeat in the form of a global wave of reaction. Just as the eclipse of the “anti-globalization” movement at the turn of the century enabled nationalists like Donald Trump to come to power by falsely presenting themselves as adversaries of neoliberalism, the eventual failure of the Gezi Park resistance enabled Recep Tayyip Erdoğan to establish autocracy in Turkey and invade Rojava—and similar tragedies have played out all around the world. This wave of reaction has taken many forms, from the consolidation of one-party dictatorships in Russia and China to nationalist electoral victories in the United States and Brazil and a resurgence of authoritarian politics among leftists.

Yet every order that does not encompass the whole inevitably gives rise to its own opposition. Years of bare-knuckled capitalism have fostered a bitterness that has yet to find a political outlet. While a minority of people have gravitated to outright fascism, greater numbers have lost faith in electoral politics altogether without finding an alternative to invest themselves in. It’s up to us to supply a model for what they can do with their rage.

A new phase of unrest began at the end of 2018 with the emergence of the Gilets Jaunes in France. At first, this movement was hardly promising, pitting “apolitical” consumer protesters including far-right elements against a neoliberal centrist government that was trying to offload the cost of its “ecological” policies onto the working class. But over the next several weeks, anarchists and other rebels used vandalism to carve out a space where an anti-capitalist current could take hold. In the course of the following year, revolts broke out in Hong Kong, Sudan, Haiti, Ecuador, Chile, Honduras, Lebanon, Iraq, Catalunya, and elsewhere. Almost all of these were sparked by cost-of-living increases (a fuel tax in France and Ecuador, a tax on WhatsApp in Lebanon, a spike in subway fare in Chile), confirming that the economic recovery from the recession of 2008 had done little to benefit ordinary people. On a deeper level, the revolts were driven by questions about the legitimacy of authority, even if these questions assumed distorted forms such as demands for independent national sovereignty.

Just as the 2008 uprising in Greece foreshadowed the revolutions that began in Tunisia two years later, we guessed that the unrest from Hong Kong to Chile presaged another global wave of revolt. Yet in the United States, the year 2020 opened upon a political wasteland. Anarchists were exhausted from three years of scrambling to respond to atrocities, and many of those who had joined us in the streets at the beginning of Trump’s presidency had returned to seeking change via state channels—the centrists pursuing a doomed strategy of partnering with the FBI to impeach Trump, the socialists reprising their equally naïve campaign to elect Bernie Sanders president.

By the time the COVID-19 pandemic swept the world, all of these efforts had failed. Trump exacerbated the situation, seizing the opportunity to transfer billions of dollars to the richest stratum of society in the midst of the worst economic recession in living memory. Millions of people in the US, alongside billions worldwide, spent mid-March to late May in isolation contemplating their own mortality and seething at their rulers’ cruelty. It had never been clearer that the institutions of power are fundamentally destructive to the lives of ordinary people.

When video circulated depicting the senseless murder of George Floyd at the hands of Minneapolis police, those who suffer most from racism and poverty recognized that it was now or never. Heroically, all around the US, they staked their lives in an all-out attack on their oppressors—and millions of stir-crazy people of all classes and backgrounds joined them in marching through cities, attacking police, burning police cars, blocking freeways, and looting shopping districts. In the midst of the pandemic, even white middle-class liberals felt the tragedy of George Floyd’s death viscerally. In impacting people from all walks of life, the virus had suspended some of the mechanisms that ordinarily prevent the privileged from identifying with the most marginalized.

Trump and other politicians have expressed shock at the riots that followed George Floyd’s murder, alleging that anarchists must have coordinated them. In fact, the ruling class did more to provoke the riots than we ever could. It was the policies of the state itself that spread the collective intelligence that guided the revolt—marking police, banks, and corporations as legitimate targets and making it easy for just about anyone to understand why it made sense to attack them. Trump’s explicit support for white supremacists, his xenophobic border policies, his efforts to abolish healthcare access, his decisions to accelerate global warming, and his refusal to provide any sort of support for those threatened by unemployment and COVID-19 showed everyone that we are all facing a life-or-death struggle, not just those who are regularly murdered by police.

Perhaps the darkest hour does herald the dawn, after all.

As this book goes to press, in the United States, we are hoping that we are already past the apex of the global wave of reaction that brought Trump to power. But the struggles of the future will continue to be three-sided, pitting autonomous social movements against both neoliberal centrists who seek to reestablish the “impartial rule of law” and far-right nationalists who aim to ride out the declining phase of capitalism by redefining whose interests the state exists to serve. Both sides are advancing proposals about how to preserve capitalism and the state; they only differ over how violence and suffering should be distributed. Yet we must not make the mistake of strategizing as if we are in a binary conflict. Each of these adversaries would benefit from our concentrating only on eliminating the other one, enabling them to concentrate on eliminating us. We have to fight in ways that reveal what centrists and nationalists have in common and that show what distinguishes our proposals for the future.

The pursuit of autonomy has been central to many of the struggles of the past two years, albeit in the distorted form of a demand for independent national sovereignty. Kashmir seeks independence from India; Hong Kong seeks autonomy from China; Catalunya seeks autonomy from Spain; Rojava seeks autonomy from Syria, and the whole world—Turkey, Syria, the United States, Russia, and the United Nations—conspires to crush it. National independence—which reproduces the internal hierarchies of the imperialist nations on a smaller scale—is not the solution to these conflicts. Conflict between nations is the domain of the state, whether or not the nations in question have received formal recognition from the United Nations. Autonomy is not a matter of separating from others, but of establishing horizontal relations of mutual aid and collective defense that are strong and wide-reaching enough to deter attacks.

Likewise, as the conflicts of our age intensify, it will be tempting to resort to militarizing our movements, but this represents a dead end for the same reason that the pursuit of national independence is a dead end. In the short term, leadership in military conflicts goes to whoever can access the most arms, as we saw in the Syrian revolution; in the long term, the outcome of such conflicts is determined by whichever party has the biggest air force, as we saw in the subsequent Syrian civil war. “The force of insurrection is social, not military,” as the Italian insurrectionists wrote. Our goal should not be to compete with the state on its own territory, the field of military conquest, but to identify all the needs and desires that the state cannot fulfill—a tremendous number, today, when governments can do so little to mitigate the impact of capitalism—and take those as the point of departure for contagious grassroots uprisings that can render us all impossible to govern.

If we want revolution rather than war, we have to organize on both sides of every border. This goes for every other form of identity alongside national citizenship. We must seek to spread resistance to domination across all boundaries—national, ethnic, religious—transcending all forms of constructed identity. The only thing that could secure the freedom of Kurdish people in Rojava would be a revolution in Turkey; the only thing that could secure the freedom of people in Hong Kong would be a revolution in China; the only thing that could secure the freedom of people in Syria and for that matter the Baltic states would be a revolution in Russia; the only thing that could secure the freedom of people in Mexico and Honduras and likely Chile as well would be a revolution in the United States, just as the only thing that could secure the safety of Black people in any of those countries would be the abolition of all the different forms of policing that maintain the privileges known as “whiteness.” We have to intensify our efforts to build connections across all of these gulfs alongside our efforts to build the capacity for collective self-defense, understanding these two projects as one and the same.

The state excels at concentrating, subsuming, subordinating, and dividing. To stand a chance against it, we must act like a hydra—dispersing, reproducing, connecting, and proliferating.

This book is comprised of our reflections on the struggles we have participated in over the past decade—our efforts to learn from our successes and failures, to identify the real problem at the root of each situation, to make the most of our tremendous potential on our own terms. May it serve you in your own efforts to do the same.

As some of us wrote at the turn of the century, when the world was young, the best reason to be a revolutionary is that it is simply a better way to live.

The backstories of the various contents of the book follow, by section.

—Anarchy—

We published To Change Everything at the beginning of 2015 in collaboration with collectives on five continents. The idea was to offer an accessible introduction to anarchist ideas.

Altogether, approximately 250,000 print copies of To Change Everything circulated in over 30 languages. We helped the publishers in Brazil, Argentina, Romania, and Slovenia to fund their print versions. Versions in Arabic and Farsi were distributed along the Balkan route during the so-called “migrant crisis” of 2015; we also arranged for prisoner support groups to send thousands of copies to prisoners in the US. To our knowledge, it seems to be the only anarchist text printed in Maltese.

—Revolutionary Movement—

This selection of texts concentrates many of our conclusions about movement strategy and ethics, accumulated in the course of a period that saw the shape of protest in the United States change dramatically.

We published “The Illegitimacy of Violence, the Violence of Legitimacy” in March 2012, during the waning phase of the Occupy movement, in response to liberals like Chris Hedges who attacked some participants for concealing their identities from surveillance and defending themselves from police attacks. Hedges’s rhetoric reappeared verbatim in the mouths of the authorities that May, when they made statements to the media explaining FBI efforts to entrap activists in Cleveland and Chicago. The years-long prison sentences those activists consequently served show just how useful Hedges was to US government efforts to repress the movement.

On the one-year anniversary of the beginning of the Occupy movement, we forced Hedges to debate a member of our collective in front of a thousand people in New York City. We arranged to broadcast the debate simultaneously at live showings around the country. This demonstrated that the perspective that Hedges was trying to delegitimize was too powerful to silence. Just two years later, the uprising in Ferguson confirmed that we had been right to argue that to be effective, future movements would have to be confrontational and involve anonymity. This time, many people understood why protesters were wearing masks and fighting the police.

“Breaking with Consensus Reality” appeared a few weeks after “The Illegitimacy of Violence.” It was the first chapter of Terror Incognita, a reflection on the dynamics of insurrectionary desire—the forces that can make it contagious or prevent it from spreading.

In late 2013, we published “After the Crest,” a series of articles reflecting on what anarchists can accomplish during the waning phase of social movements—beginning from the premise that, as movements tend to explode into being, they spend most of their time in decline. Only the introductory text is included here. The original series included case studies from the Occupy movement in Oakland, the student movement in Montréal, and the series of strikes, occupations, and riots that swept Barcelona between 2010 and 2012.

The uprisings against police and white supremacy that burst onto the world stage with the revolt in Ferguson in August 2014 changed the atmosphere in the United States and the way that people thought about protest movements. We published “Why We Don’t Make Demands” in spring 2015, immediately after the uprising in Baltimore in response to the murder of Freddie Gray, arguably the high-water mark of anti-police uprisings until May 2020.

“There’s No Such Thing as Revolutionary Government” and “Against the Logic of the Guillotine” appeared in 2018 and 2019, in the midst of the reactionary Trump era, when some authoritarian leftists sought to imitate the success of far right at employing populism to acquire power.

The first version of “We Fight Because We Like It” appeared in “Conflictual Wisdom: Revolutionary Introspection towards the Preservation of the Anarchist Individual & Community.” It was composed at a grim moment at the beginning of 2018, when the Trump era was just getting underway, many of our comrades were still facing the likelihood of decades in prison as a consequence of the demonstration on the day he took office, and it was not yet clear how bad things would get.

—Skirmishes—

“Music as a Weapon” represents our reflections on decades of experimentation in connecting the punk underground with the international anarchist movement. The first version of this text appeared in the Spring 2009 issue of our biannual journal Rolling Thunder. This slightly revised version appeared on our website in late 2018 when we finally grudgingly set about digitizing all the music released through the record label facet of CrimethInc. from the 1990s into the early years of the 21st century.

“The Climate is Changing” first appeared in December 2009 during the demonstrations outside the “COP-15” United Nations conference on climate change in Copenhagen. We included it in our book about capitalism, Work, which has also appeared in German. The version in this collection is a revised translation that has not been published before.

“Accounting for Ourselves” appeared in 2013. It represents another aspect of the same conversations about consent and accountability that produced “Breaking with Consensus Reality.”

“How to Stop the Police from Killing” appeared on the last day of May 2020, when the revolt in response to the murder of George Floyd was beginning to spread around the country. A zine version of the text was widely distributed at the various occupations and police-free zones of June 2020.

—Reportbacks—

We published “From Germany to Bakur” in late 2015, at a tense point in the struggle in Rojava and Turkey against the Islamic State and the autocracy of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. Tragically, in 2019, we were compelled to publish “Remembering Xelîl,” eulogizing one of the contributors to that earlier text who was killed in the process of that struggle.

“Surviving the Virus” and the follow-up text “And After the Virus?” appeared in March and April 2020, in response to the arrival of COVID-19 and the state-ordered quarantine. We feared that panic occasioned by the pandemic would drive people to embrace authoritarian politics, imagining strong top-down control to be the only way to avert to mass casualties. Instead, state governments from China to the United States botched their responses to the pandemic, while grassroots networks emerged around the world to organize mutual aid projects according to anarchist principles. To our surprise, “Surviving the Virus” reached hundreds of thousands of people in sixteen different languages. Apparently, people were hungry for an anarchist alternative.

Finally, “The Siege of the Third Precinct in Minneapolis” offers a participants’ analysis of the historic attack on the police precinct in May 2020. We published it in early June at the high point of the movement responding to the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and countless other Black people. It represents a necessary corrective to subsequent liberal mystifications of the movement that seek to conceal how multiethnic, decentralized, confrontational tactics were essential elements in its most important victories.

We can fight the police and win. We can organize our own means of survival and face down the state. Together, we can take hold of our tremendous untapped potential and create the lives we deserve to live. Never forget this.

“Become ungovernable,” a stencil included in the book.