Last week, the Student Workers of Columbia (SWC) reached a tentative agreement with the university administration, voting to end one of the longest strikes in the history of graduate worker organizing. After over nine weeks on the picket line, the strikers forced the administration to concede to all of their major demands. Yet the strikers were only able to achieve this victory because they had already confronted and defeated the union bureaucracy that sought to stop them from confronting the administration. Their victory shows that workers who seek to assert their interests in the workplace must begin by fighting for self-determination and grassroots power within workplace organizing itself. Read on to learn the whole story of the strike at Columbia.

As of last month, the strike by the 3000-member graduate worker union at Columbia University was reportedly the largest strike action in the entire United States.1 This hints at the extent to which old-fashioned mass union militancy has receded since its heyday in the 20th century.

In some ways, graduate students are emblematic of the new shape of the workforce. Graduate student organizing occupies what a grad student might call a liminal space between school and the workplace: graduate students are workers, but they have yet to join the workforce proper. They are not the only workers whose jobs are fundamentally temporary and transient; today, there are entire industries that will no longer exist by the time the next crop of graduate students receive their diplomas. Universities justify the low wages they pay graduate workers by describing them as students, not workers, gesturing at their supposed future employment prospects—which in fact will only be available to a shrinking number of graduates in an increasingly competitive market rapidly being reshaped by austerity measures. In this regard, the pyramid scheme of higher education is a microcosm of the pyramid scheme of capitalism itself.

Yet seeking to defend the security of a particular demographic of student workers without concern for other workers or students is a doomed venture. Graduate students are not essential to the industrial economy in any strictly material sense. In order to exert any leverage on the administration that employs them, they must apply pressure in concert with others who are being squeezed at least as badly as they are. Twenty-first century capitalists have restructured the economy in order to render workers in practically every industry replaceable. In this context, behaving according to the old Industrial Workers of the World slogan “an injury to one is an injury to all” is a strategic as well as ethical necessity. For labor struggles to have teeth in this brave new world, those of us whose jobs and lives are becoming ever more precarious will have to forge new alliances across demographics and workplaces.

In the following analysis, participants in the graduate worker strike at Columbia recount the entire story, blow by blow, and distill the lessons for students, workers, and rebels everywhere.

Columbia’s Graduate Worker Union Struggle, 2004-2022

The full history2 of graduate student worker organizing in the US remains to be written. This story is complicated by differences between workers at private universities, which are subject to federal labor law, and workers at public universities, which are governed by state legislatures. For public universities, whose employees don’t qualify for federal labor law recognition due to the provisions of the Taft-Hartley Act, policies vary by state according to political climate and local circumstances.

At private universities such as Columbia, grad worker organizing was hamstrung by administrative and court rulings until quite recently. In 2000, grad workers at New York University (NYU) became the first at a private university to achieve union recognition when the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), the government agency tasked with interpreting labor law, overturned decades of precedents forbidding grad worker unions. The newly recognized UAW-affiliated union at NYU immediately won massive gains in its first contract, including a 40% pay increase plus benefits and other protections.

However, in 2004, the NLRB (having been reappointed under the Bush administration) reversed its previous ruling. The Board declared that the Brown University grad workers fighting for union recognition were not eligible for collective bargaining because their status defined them “primarily” and “first and foremost” as students—not employees—with their compensation defined as a form of “financial aid.” NYU promptly un-recognized its grad union, provoking a bitter grad worker strike. In response, the administration both punished the strikers and offered grad students financial aid increases while cutting their representatives out of the decision-making process.

Yet in 2016, as the political winds shifted once more and another decade of grad worker organizing raised the pressure, the NLRB once again reversed its reversal, ruling that Columbia grad workers did in fact have the right to unionize and collectively bargain. This opened the floodgates for grad workers at private universities, resulting in union recognition and contracts at Brandeis, Tufts, Georgetown, and Harvard, with many more under negotiation.

The Strike of 2018 and the Strike Ban

Columbia’s effort to unionize had begun in 2004 alongside the controversy over the Brown decision. Energized by the decision of the NLRB in 2016, the as-yet-unrecognized union at Columbia undertook a strike in spring 2018. This lasted for a week—a template set by their parent union, the United Automobile, Aerospace, and Agricultural Implement Workers of America (UAW), which generally aims to keep strike actions predictable and within budget.

The strike of spring 2018 garnered considerable media coverage. Morale was high. Yet as it lasted only one week, the university was able to ignore it. The members met to debate whether to extend the strike, but a poll suggested that there wasn’t enough support to do so. They returned to work without making significant headway.

The outcome of that strike reflected longstanding divisions that the UAW repeatedly exploited to moderate the form and agenda of strikes. Columbia includes several schools and many departments, which can be broken down roughly into STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) programs and humanities and social science programs. Although a substantial proportion of organic rank-and-file participation in the union campaign emerged from workers in the humanities and social science programs, the repeated refrain that it was necessary to rein in demands to avoid alienating the STEM workers helped keep a lid on more radical aspirations among the rank and file. In the words of one rank-and-file member, the UAW successfully used this division as a strategy to manage union militancy.

In fall 2018, momentum built towards a larger and longer strike scheduled to begin that November. Just days before it was to take place, following secret negotiations with UAW officials, the administration announced a proposal to formally recognize the union and begin negotiating a contract in exchange for a pledge not to strike for 16 months, demanding an immediate response. This bitterly divided the union, which voted by a thin margin to accept the proposal and the strike ban. Negotiations began in tense, lengthy meetings between the bargaining committee, administration officials, lawyers, and a handful of rank-and-file observers.

Interlude I: On Graduate Worker Organizing

Imagine an average twentieth-century workplace: generally speaking, one could assume that the longest-hired employees would be the most informed about organizing efforts and the most invested in the outcome.

The trajectory of grad student careers creates the opposite dynamic. The student organizers who have been in the fight the longest—the ones who are in their fifth, sixth, or seventh years—are on their way out the door. They’re not going to benefit from the contract that will be achieved through the negotiations; whether or not they succeed in getting an academic job, their time as grad students is coming to an end. Meanwhile, the incoming grad students—the ones who have the most at stake in the contract, because they’ll be subject to its terms for years to come—know the least about the union, the university, and the struggle.

Consequently, the interests of the most experienced organizers differ from the interests of those who have to live under the contract that results from their organizing efforts. The old-timers want to wrap things up with a long-awaited success under their belt; they’re also exhausted, burned out, and on their way out the door. This gives them an incentive to compromise and accept terms that they might not accept if they themselves had to live under them.

On the other hand, for the most part, the incoming grad students—the ones who stand to gain or lose the most from the negotiations—haven’t been around long enough to become well-connected activists or members of the bargaining committee (the grad worker activists who are elected to represent the union). We saw this disconnect in the November 2018 vote, when nine tenths of the bargaining committee advocated in favor of the controversial strike ban deal, while nearly half of the rank-and-file opposed it.

Likewise, the UAW, a major international union with almost 400,000 members across 600 locals, has its own interests—which may or may not align with those of the grad workers themselves. As critics of union bureaucrats have long argued, when the financial and power structures of unions begin to look similar to those of the employers and governments they’re supposedly challenging, it’s likely that their interests will line up with them rather than with the workers they claim to represent. As Student Workers of Columbia (SWC) was negotiating their contract in 2019, UAW president Gary Jones was arrested for helping himself to over a million dollars embezzled from the retirement funds of autoworkers; he began a prison term at a cushy minimum-security facility at the end of 2021. UAW higher-ups accustomed to their steak dinners and golf trips at workers’ expense need to keep those union dues pouring in. They have a financial interest in getting grad workers to accept even a crummy contract. Rank-and-file power is a threat not only to employers, but also to the union officials who see workers as a constituency to be mobilized for political capital and a cash cow to fund their salaries.

After years of union activity, outgoing grad workers are the ones who are most likely to have absorbed the influence of UAW organizers. In some cases, they have been paid by UAW to organize their departments. They are the most likely to favor bureaucrats up the chain of command calling the shots in negotiations with the administration and decision-making within the union.

This context is essential to understanding what happened next.

The Betrayal

The bargaining began in February 2019—and stretched out interminably. Insulated by the no-strike pledge they had coerced the union into accepting and represented by an arrogant anti-union law firm (whose pockets were lined with more Columbia cash every day they could drag out the process), the administration had little incentive to offer any concessions over a year of negotiations. In early 2020, with the strike ban set to expire in April, union organizers began gearing up for a spring strike.

But then COVID-19 hit. In New York City in particular, the impact was devastating. Classes were canceled, hundreds became ill, and a fitful shift to remote teaching through Zoom took place over March and April. With the strike ban expired, some organizers proposed going ahead with a strike despite the chaotic situation, but a majority demurred, disagreeing strategically or simply too sick, stressed, and scared to try it. Internal conflicts flared up within the union and personal attacks flew. A small end-of-semester strike did take place, securing crucial summer pay-bonuses for those on nine-month appointments. This was the first of many participatory actions that drastically increased involvement in the union. But with the nationwide explosion of racial justice and anti-police protests prompted by the killing of George Floyd, many of the most politicized union activists shifted focus to the mutual aid, street protest, and community organizing efforts that marked the long hot summer of 2020. Meanwhile, the post-doctoral workers, whose separate union had long organized alongside the larger grad worker union, successfully negotiated a contract that met their major demands, splitting off a segment of the mobilized workforce.

The fall semester saw the election of a new bargaining committee, with sharp conflict between factions advocating different visions of how to move forward with the negotiations. A group of students with some union overlap attempted to organize a tuition strike addressing a broader range of demands, including increased financial aid, slowing gentrification, defunding campus police, and fossil fuel divestment as well as the union’s contract demands. In spring 2021, as negotiations sputtered and the union struggle resumed once more, this expansive radical vision receded into the background, one of the missed opportunities of the broader struggle.

As the spring semester of 2021 unfolded, with students and workers once again returning to Zoom, momentum began to build once more towards a strike. But how would it work? How do you withdraw labor from a virtual workplace? What would picketing look like? Would the impact be sufficiently disruptive to exert leverage on the administration? Despite many questions, the frustration of two fruitless years of negotiations stimulated an active strike campaign.

The strike began on March 15. The university set up a surveillance system to dock pay from strikers by forcing all workers to “attest” online—in other words, to digitally scab—in order to receive wages. The provost, the administration official heading up the negotiations for the university, was a progressive historian and political scientist with a long record of labor advocacy; this led some to (incorrectly) predict that the university might be more willing to bend in the face of the disruptive power and negative publicity of a strike. Lively daily pickets took place on the physical campus, while an online “virtual picket” on Zoom provided another option to strikers and supporters near and far.

Two weeks into the strike, the bargaining committee submitted a proposal to the university that included significant compromises on many of the union’s critical demands. Concerned rank-and-file members began organizing on their own. In early April, in the third week of the strike, the bargaining committee announced that it would accept an administration proposal to “pause” the strike and enter into mediation—without receiving any substantive concessions or guarantees of back pay in return. A general body meeting of 300 union members voted 75% against the proposal, but the bargaining committee voted 7 to 3 to accept it anyway, disregarding the rank-and-file majority.

A furious debate ensued. Many individuals and some entire departments continued striking, despite the bargaining committee’s declaration of a “pause.” Rank-and-file organizing continued, with countless meetings, demonstrations on campus, and actions within departments. It became increasingly clear that the bargaining committee was out of step with the most mobilized sectors of the union’s rank and file. This was dramatically illustrated on April 19, when the university and the bargaining committee announced that they had reached a tentative agreement—one which did not substantively meet any of the three major demands regarding compensation and benefits, neutral arbitration, or full unit recognition that had been identified as the unit’s core priorities.

This sell-out contract baffled many rank-and-file members. It’s only possible to make sense of it if we understand the reactionary tendencies of bureaucratic unionism and the peculiar circumstances of grad student worker organizing. The seven bargaining committee members who agreed to the contract were about to complete their time as grad students and move on to new jobs; they would not have to deal with the consequences of their failure to secure what the union’s members demanded. The UAW officials showed their true colors repeatedly, as they spoke out against the efforts of NYU and Columbia units to coordinate their efforts. The way that the UAW’s interests diverged from rank-and-file workers was obvious in the financial nuts and bolts of the tentative agreement. On paper, the raise coming to grad workers looked significant, if less than hoped for—until union dues were figured in. Once you subtracted dues and adjusted for inflation, the new salaries actually amounted to a pay cut for grad workers. The bargaining committee got their “victory,” the UAW got the university to subsidize 3000 new dues-paying members… and the rank-and-file workers got sold out.

As the spring 2021 semester drew to a close, a ferocious struggle unfolded over the ratification of the contract. While the UAW and the bargaining committee could do practically whatever they wanted without the broader consent or participation of the rank-and-file, one thing they couldn’t do was approve the contract. Rank-and-file activists waged a campaign to vote down the sell-out contract. The union members who supported the contract defended this as “pragmatism,” arguing that the university was too stubborn to give any more ground than the strike had already forced them to cede. Since the bargaining committee and the university controlled all forms of top-down communication, including mass emails and social media posts, it took substantial bottom-up organizing to argue in favor of rejecting the contract and continuing to fight.

Despite the ways that the odds were stacked against the rank and file, when the votes were counted, the sell-out contract had been rejected by a narrow margin. Columbia and the UAW were shocked: a rank-and-file vote to reject a contract is virtually unheard of in labor disputes. The university retaliated by bad-mouthing the union membership and attempting to discredit the vote, but they went further: over the summer, the human relations department announced that it was unilaterally restructuring the pay schedule for grad workers, allowing them to withhold three times as much pay in the event of a new strike.

The bargaining committee resigned en masse. At the end of the summer, a new committee was elected that promised not to sell out the rank and file. The summer also saw the union adopt a new constitution enabling more extensive rank-and-file participation and including accountability mechanisms to prevent the new bargaining committee from unilaterally ending or “pausing” a strike. The mobilization provoked by the sell-out agreement proved enduring, with major consequences for the next round of struggle.

Unexpectedly, the conditions that the pandemic introduced provided a major impetus to the rank-and-file participation and radicalization that emerged in 2021. Until then, bargaining sessions had occurred in person, usually off campus and in the middle of the day; while technically open to the rank and file, they were inaccessible to average members. The shift to online meetings rendered the negotiations much more accessible, and offered multiple channels of simultaneous communication; dozens or even hundreds of rank-and-file members could attend and use the Zoom chat function, Dischord channels, or WhatsApp groups to vent, gossip, and strategize in real time.

This became particularly significant during the strike, when hundreds of workers whose afternoons were suddenly open began to attend—especially since UAW policies mandated either physical picketing or virtual participation (including attending bargaining sessions) to qualify for strike pay. Consequently, hundreds of workers who had never seen the bargaining process in real time before witnessed the arrogance and intransigence of the administration and its lawyers—and the way that most UAW-affiliated bargaining committee members were making compromises at the expense of the rank and file. Without this digital accessibility and expanded communication, it’s hard to imagine that the rank-and-file organizing to reject the sell-out contract and transform the union from within could have succeeded. A new cohort of rank-and-file activists who met on the picket lines and in virtual meetings and bargaining sessions became radicalized and stepped into greater organizing roles, particularly in the fall. Many of them were earlier on in their programs at the university.

Interlude II: On Demands

This account of the struggle at Columbia does not focus on the specific demands put forward by the union over its years of struggle. This is in part because the particular content of demands changed significantly over time. The core demand for the first decade of organizing centered on union recognition, which was viewed as an essential step towards addressing a wider range of demands through collective bargaining. UAW organizers and activists established working groups to document issues and establish bargaining positions around issues including late pay and concerns particular to parents with children, international students, and other demographics. The focal point of demands shifted as some were successfully addressed administratively or through bargaining.

By the time of the strike in the spring of 2021, three key areas of deadlock were emerging: around compensation and benefits (specifically increased stipends, dental and vision insurance, and child care subsidies), full unit inclusion (recognition by the university of all workers, including undergraduates, who were legally entitled to join the union), and neutral, third-party arbitration in cases of sexual harassment and misconduct. The latter issue became the most prominent and emotionally charged issue in spring 2021, as Columbia has experienced several disturbing public scandals around rape, assault, and sexual harassment by faculty members and employers towards graduate workers. These issues carried on into fall 2021, combined with questions about “union security” (whether grad workers would comprise an “open” or “closed” shop), to form the linchpins of union communications and agitation.

While the specific content of these demands provided useful points of mobilization at different times, the more significant issue pertains to how and by whom the contours of the struggle were determined, including not only demands but tactics, strategy, and modes of organization. The original approach introduced by UAW organizers was reminiscent of the Maoist “mass line” strategy, in which leadership listens to the concerns of “the people,” formulates a program based in these concerns, then diffuses that program back to the masses. By contrast, in the later phases of the struggle at Columbia, the union’s shift towards self-organization entailed much substantive rank and file participation in setting the content and priorities of the negotiations through open meetings and caucuses, consistent polls, and other means. Through this process, the gap between “leadership” and rank and file narrowed, ensuring that the interests of the bargaining committee could not dramatically diverge from those they claimed to represent as it had at earlier phases. As the university’s steadfast refusal to concede even around issues that involved no direct financial stakes showed, the central issue always centered on power—not just who gets paid how much, but who gets to decide. In this struggle, the demands themselves were less important than the parallel struggles, both of the union against the university and within the union itself, for power and self-determination.3

The Showdown

In fall 2021, students and workers returned to campus in person for the first time since the pandemic began. This decision, unevenly imposed on workers in different departments and sectors of the university with little input, led to grumbling—and in some cases, organizing—across the university. The purportedly pro-labor provost was gone, replaced by a bureaucrat who was accurately predicted to be actively hostile towards the union effort. She faced off against a new bargaining committee that was determined to avoid the compromises and failures of spring 2021. The stage was set for an even fiercer round of conflict—this time, playing out on the physical terrain of in-person classes, which are more vulnerable to physical disruption through picketing and protest.

Bargaining resumed, but all sides knew that a strike would not be long in coming.

On November 3, 2021, the new strike began. It was to become the longest massive strike in the history of grad worker organizing, and ultimately more successful than the organizers could have dreamed. The university set the tone with increased pay docking, increasingly hostile communications laced with misinformation from the provost, and efforts to turn the faculty, the student body, and the community at large against the union. The strikers mobilized networks of campus and community supporters, raised a “hardship fund” to support economically vulnerable workers, maintained daily pickets on the campus, and organized creative protest actions. Each week, the union sent out a poll to gauge interest in continuing or ending the strike. One week after another, the results indicated that people wanted to continue to fight.

After a month, the strike had wrung some concessions out of the administration, but they appeared to be willing to put up with bad press and labor disruption in order to wait the grad workers out. As economic stress mounted, the union considered options to raise the pressure. At the beginning of December, the university escalated: the HR department sent a message threatening to withhold spring appointments from striking workers—in other words, to fire and replace them. More than any other action, this catalyzed outrage across campus. The following Monday, a gigantic rally featuring dozens of faculty supporters clogged the campus, and on Wednesday, the union conducted a daylong disruptive protest with pickets at every entrance to shut the campus down. [See the account below.] The university panicked. Even as the administration condemned the union in a shrill tone, it also offered its most substantial concessions up to that point, showing the power of direct action.

The semester drew to a close, yet the parties still remained in a standoff. An outside mediator was brought in, but this time, the bargaining committee refused to “pause” the strike, having learned from the mistake the previous spring. The bargaining committee offered concessions, but weighed them carefully in open caucuses first, supplementing those with polls soliciting input on what the most important priorities were and which issues were non-negotiable. The university offered several “final” proposals, but when the administration failed to address key demands, the union held firm. Week after week, the polls showed high support for continuing the strike.

The semester ended with hundreds of teaching assistants refusing to submit grades. Despite their threat to lock out strikers in the spring, the administration could not possibly hire enough scabs to take on all the different kinds of labor that the strikers were responsible for. The administration’s resolve was crumbling.

Finally, as the new year arrived, over nine weeks into the strike, the university bent and finally broke over its last areas of defiance. The tentative agreement now on the table for ratification substantively addresses all of the union’s major demands. It is very different from the agreement that the administration and the UAW tried to foist on the union last spring.

The victory in this struggle is remarkable, not only because it is a successful union struggle in a time when those have become rare, but because it shows the importance of an internal struggle for self-determination over the conditions of decision-making both with employers and within the union itself. The new contract’s material gains, which would have been unimaginable had the union stuck to the strategy of the UAW and the pragmatists, are the consequence of self-organized action against the university and against union bureaucracy. We hope that the effects of this victory will ripple out into struggles in other campuses and workplaces, informing other movements and contributing to a deeper transformation of the university itself.

Self-determination on a horizontal basis is not just the goal of our struggles—it’s the only way to make progress at all.

“We Have Teeth”: An Account of the Columbia Graduate Student Strike

The following account was written by a rank-and-file anarchist participant in the SWC strike in mid-December.

The Student Workers of Columbia, UAW Local 2110, are entering our sixth week of striking as I write this. This follows on the heels of a three-week strike this spring and a vote to reject the contract we were offered—which itself built upon nearly two decades of organizing to establish this union, force the administration to recognize it, and bargain over the issues. This account represents my perspective as a participant, an anarchist, and a rank-and-file member of the union.

The issues that led to the strike are easy to sum up. We’re demanding:

1) a living wage, with adequate benefits and child care provision; 2) neutral third-party arbitration in cases of sexual harassment and misconduct, as opposed to the broken internal system that the university offers to discipline itself; and 3) recognition by the administration of all the workers who are legally eligible to join our unit.

There have been gestures towards a “NYPD off campus” provision like the one that New York University graduate workers have fought for, but it doesn’t have much traction, at least not yet. But the strike has implications beyond our campus: it is also a fight for student worker unions in general and the labor movement as a whole.

As I write this, we’re hearing that this is currently the biggest strike happening in the United States. What does that mean for us? For the labor movement? For the economy more broadly? What can (and can’t) strikes do today? And what does this struggle suggest about broader prospects for liberation? Here are a few notes from the front lines.

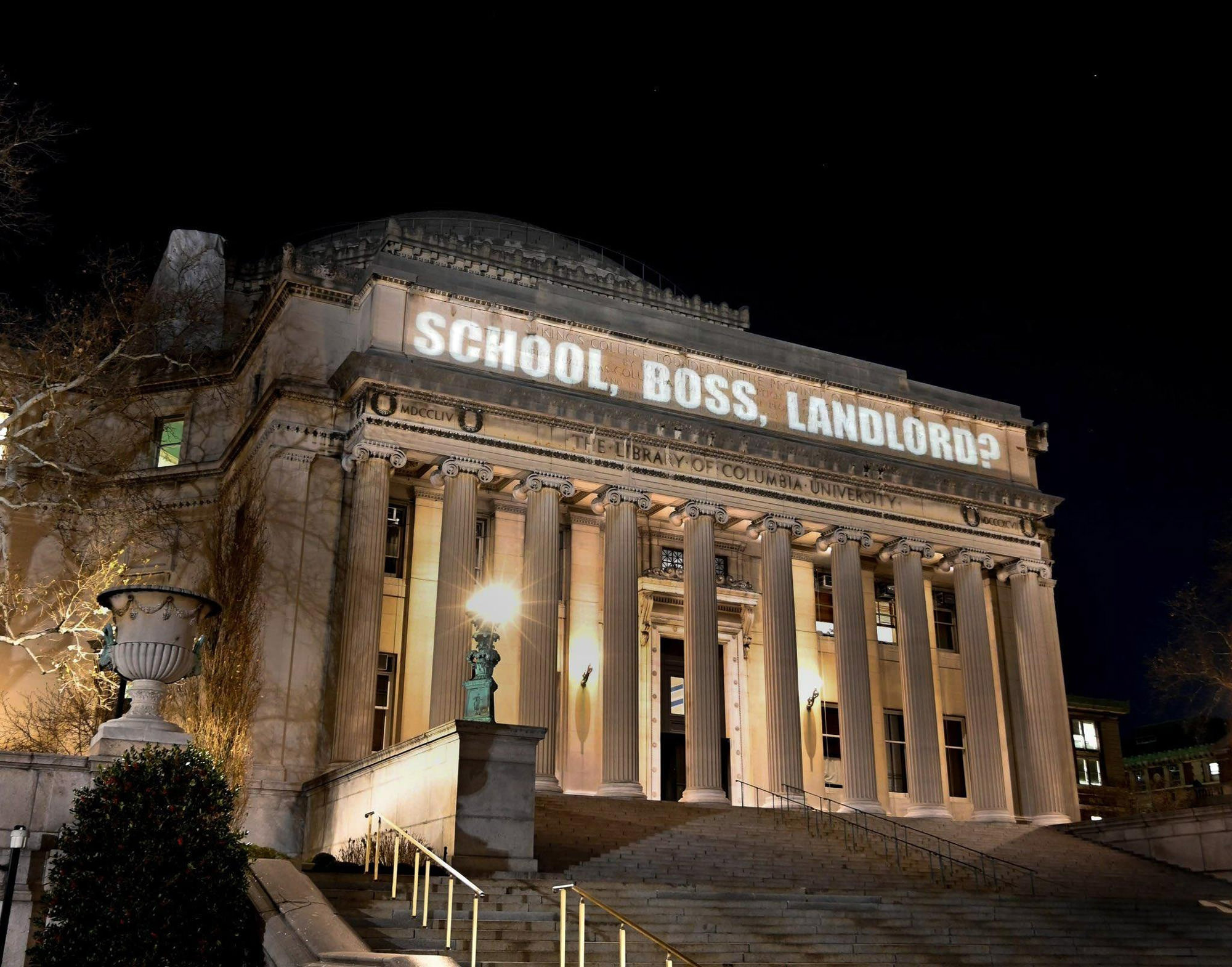

First, let’s get one thing straight. Don’t be fooled by the name: Columbia is not a “university.” It’s a real estate company that offers classes and degrees to boost its prestige. On the island of Manhattan, one of the most expensive markets in the world, it owns the second highest amount of property. It is second only to the Catholic Church, another real estate company posing as something else. This is appropriate enough for an institution named after the guy who kicked off the whole idea of land as something that can be owned in this hemisphere.

Columbia’s fancy words about its educational mission are not meaningless, though. They have a very specific meaning, which serves to add value to its brand. By posing as a socially responsible institution with a rigorous commitment to academic excellence, Columbia can mask and justify the astronomical profits it extracts from the land and people of New York City.

It’s well known that the entire academic industry has been undergoing a neoliberal contraction in recent years. As in many industries, more and more jobs are switching to “contingent” and adjunct status: less pay, less job security, fewer benefits, etc. Economic logic and profit motives drive the distribution of resources among departments and schools more than ever—not that we should buy into some fantasy of a pure liberal arts utopia unsullied by crude materialism, which has never existed in this country.

Columbia is imposing its own version of austerity on faculty, staff, and students across the board. But in this struggle, despite what the administration claimed early on, the administration’s objections aren’t fundamentally about what our proposals will cost. Amid the strike negotiations, Columbia announced its assets had increased by $3.3 billion (yes, with a “b”) over the last COVID-stricken year, which rather dampened their claims that they couldn’t afford inflation-adjusted raises or dental insurance for their workers. Not to mention the countless thousands of dollars they’re shelling out to the top-shelf anti-union corporate law firm Proskauer Rose to fight us tooth and nail. Instead, they shifted their rhetoric to emphasize what they think is “fair” or “reasonable,” according to whatever undefined standard they imagine.

In other words, it’s about power. What matters to them is not what it costs, but who gets to decide. An institution controlled by wealthy trustees and administrators, even if it has to sacrifice short-term profits, is preferable to one controlled by its workers, students, and the community where it is located. That’s why it’s so important for this real estate company that drips money from every pore to fight relentlessly against not only nickel-and-dime demands regarding childcare and benefits, but also the minutiae of the processes by which we try to hold accountable the faculty and bosses who harass us.

What do you do in the face of such a concerted campaign to maintain control? The union has framed the withdrawal of our actual labor as the chief weapon we have. That’s certainly something; even without all of our membership participating in the strike, we’ve made teaching, grading, research, and other aspects of the maintenance of the “university” into headaches. As a result, the administration has escalated their threats, threatening to fire us or lock us out from spring teaching appointments if we don’t break the strike and threatening to deny undergraduates credit for their classes in hopes of turning them against us.

But the idea that withdrawing our labor is the best way to exert leverage hinges on the assumption that Columbia is in fact a university first and foremost, they way it represents itself to be. If we shift our analysis to account for the fact that Columbia is a real estate company that offers degrees, new things come into focus.

The “university” function of this real estate company isn’t irrelevant in this model. But the question becomes: what arrangement of this university function will allow Columbia to keep its underlying economic model running smoothly while preserving the legitimacy afforded by its Ivy League mask?

I can imagine a few dystopian versions in which graduate students are rendered redundant in the push to austerity. At the University of Chicago and NYU, administrations tried to buy off grad students with cushy stipends that didn’t actually require work—on the condition that they remain (docile) students and not unionize. Where endowments don’t permit such tasty carrots, other universities—especially in more union-hostile regions—will rely more on the stick to keep student workers in line. Here at Columbia, I think we’ll probably win this particular battle and get a contract we can live with. But in the longer term, mark my words, this institution and its peers are laying plans to decenter student labor.

Looking at the situation through this lens has shifted my sense of what’s interesting about our struggle here.

Last Wednesday [December 8, 2021], hundreds and hundreds of union members, undergraduate students, faculty supporters, and activists from across the city converged on campus to shut it down for the day. Every entrance to the main campus was clogged with a lively demonstration, with hundreds of protesters cycling in and out and people aggressively confronting those who crossed the picket line. People still came and went, but the campus felt eerily deserted, and even those who did cross the picket line felt compelled to justify their actions. The union had inverted the sense of entitlement that usually characterizes students’ everyday relationship to the territory. People brought drums, banners, meals, media, and even one of the dramatic inflatable animals from the Teamsters that exemplify the visual landscape of New York City labor.

Some of the most interesting actions took place among small crews focused on stopping deliveries. A knot of protesters sat by a spigot all day to turn away the Teamster driver who came to refill the university’s oil supply. An Amazon employee organizer came out and networked with the strikers, and protesters swarmed Amazon, UPS, Fedex, and other drivers. Not all of the stoppages were successful, but many were; the infrastructural underbelly of the university faced more scrutiny and disruption than I had ever seen before.

Up until that point, the administration’s communications about the strike had been relatively restrained, if self-interested and misleading. But the campus shutdown made them panic. Multiple full-campus emails flew around raising the alarm, encouraging students to ask campus cops to help them cross picket lines, accusing the union of violence, and generally spreading panic. It seemed that many hundreds of us withholding our labor for weeks was annoying but tolerable—but interrupting the flow of bodies and goods for a day genuinely shook them.

Of course, plenty of students were pissed off, too. In one hilarious exchange I witnessed, a white guy with a Young Republicans haircut was crossing the picket line. As picketers yelled, “Don’t cross!” he retorted, “Don’t block!” When one striker replied, “Fuck you!” he sneered: “Get a job!”

Apart from the comical ignorance of this wayward bro telling striking workers to get a job at a labor protest, there’s something else going on here. For a generation of reactionaries, protests have been associated with unemployed and unwashed hippies, malcontents looking for a handout, resenting the hard-working and successful to mask their own failings. The anti-war movement of the 1960s set this template so powerfully that even conservatives born decades after it still conjure up this trope—bolstered by more recent conspiracy theories about unemployed protestors paid by George Soros or some other shadowy force. Many conservative people can only understand protest through that frame, even a protest like this—which wouldn’t be happening if the protesters didn’t have jobs. Ignorant and self-serving as it is, this reading reflects the anxiety of the wealthy regarding the threat that the poor and unemployed pose to their power.

Another reading, specific to this context, could be that the strikers are not really “workers,” but students (in theory, these are mutually exclusive categories, though in practice, they almost never are). This was Columbia’s line from the beginning—until the National Labor Relations Board refuted it and forced the administration to recognize the union—but the power of the rhetoric remains. In telling us to get a job, the bro could have meant that we should get “real” employment instead of complaining about our conditions in our intermediate state. Of course, not only are we “really” employed in our current jobs, but graduate students are routed into a shrinking bottleneck of professional and academic jobs that become more contingent and precarious every year. No matter how hard-working and diligent we are, even with all of our Ivy League advantages, the economy won’t structurally permit most of us to take that bro’s advice.

One of the funniest recurring chants that marks the pickets and demonstrations is “WE HAVE TEETH!” This alludes to our demand for dental insurance; it has the advantage of being funny, universal, and intimately relatable. There’s an undercurrent of irony, though, in the way it plays on its metaphorical meaning. For something to “have teeth” means it has force behind it. To say we have teeth is to convey that we are making a threat that we can follow through on, that we’re not fucking around.

One of the ways to deal with anxiety is through laughter. The humor in this chant is inflected with anxiety—we have teeth, sure, but does our struggle? Does our strike have the force behind it to force the university to meet our demands? And even if we do win, does our collective power as students, workers, future academics, etc. have enough “teeth” to matter, as neoliberal policies drain the universities of resources and austerity advances on multiple fronts?

Myself, I’ve never had dental insurance in my adult life. Have you ever waited in line at the monthly poor people dental clinic for hours, only to be told at the end that your number didn’t come up? I have, more than once. So the idea that I could get a PhD and go to the dentist too sounds pretty appealing. But is this a prelude to a more secure dental life? Or the last gasp of a movement that is unlikely to secure us a ticket back into a dentist’s chair after graduation?

I think the answer depends on where we see our power and whether we strategize accordingly. Can we shift from imagining that our (precarious, replaceable) labor itself is the source of our strength, to concentrate on building a collective capacity to disrupt the everyday functioning of capital in the university and beyond? A single day of physically disrupting students, workers, and deliveries seems to have made more impact than five weeks of striking, judging by the university’s communications and also by the announcement that Columbia made at the bargaining table the following day—when they offered the biggest economic concessions they ever have.

There’s a lot that we can learn from this. In this brave new world, our labor is no longer the source of our power. But the relationships we make in the course of standing up for ourselves—across the lines of position, workplace, and identity—could be the basis for a strike power that exploits the vulnerabilities of infrastructure by targeting bottlenecks in the flow of people and economies. Our enemies are more concerned with preventing us from building collective power than they are with any particular economic concessions. They know that it’s worth a short-term investment to preserve their rule in the long term—and that they can always route around us, in the future, if we remain intractable. They’ve done it before, buying off whole generations just long enough to regain control.

As the climate collapses, mass surveillance spreads its tendrils ever deeper into our lives, economic disparities intensify, and fascism rears its ugly head, time isn’t on our side. We can’t just shut down our workplaces; we have to shut down the whole economy. That’s what it’ll take to strike with teeth. And our teeth—not to mention our lives—depend on it.

Further Reading

How to Strike and Win, by Labor Notes

Unions Against Revolution—A critique of trade unions and syndicalist unions from a communist perspective, by G. Munis

Up against the Wall, Motherfucker—The Game? Revisiting a Simulation of the 1968 Occupation of Columbia University

-

In fact, considerably fewer than all 3000 members were participating in the strike at any one time. ↩

-

As early as 1968, teaching assistants at the City University of New York were the first to be included in a collective bargaining agreement, their cases included with the faculty union’s contract, while University of Wisconsin at Madison teaching assistants were the first to achieve independent union recognition with their successfully negotiated contract in 1970. At the University of Washington, graduate student workers began organizing as early as 1963, but were not granted formal recognition with collective bargaining power until 2004. A proposed California state law that would have mandated state universities to recognize graduate worker unions was defeated in 1984, but after many years of fierce battles at the University of California at Berkeley and other campuses, a United Auto Workers-affiliated union was recognized in 1999—though radical student organizers argued at the time that union bureaucrats and university officials kept control of negotiations without accountability or rank-and-file participation. In other states with legislatures more hostile to unions, graduate student workers still lack collective bargaining rights, organizing in associations that their employers refuse to recognize. As of 2004, for example, 23 states banned all public employees from unionizing, while others specifically excluded grad workers from collective bargaining rights afforded to other university employees. Generally speaking, grad worker unionization succeeded on several campuses in the 1970s, stalled in the Reagan years, but surged again in the 1990s; all this time, however, grad workers at private universities were forbidden recognition. ↩

-

For further reflections on the limits of demand-based politics within social movements, read “Why We Don’t Make Demands.” ↩